In the past decade, a plethora of data-driven material modeling methods have been proposed based on existing machine learning techniques, such as deep neural network (DNN), recurrent neural network (RNN), Kriging methods, clustering analysis and proper orthogonal decomposition. Enabled by recent progresses in computer hardware systems (e.g. GPU) and open-source libraries (e.g. Tensorflow and PyTorch), neural network-based methods become the most popular ones due to its large model generalities (see the universal approximation theorem).

However, an issue that lots of us may have encountered when experimenting on neural networks is "the danger of extrapolation". It means the learned model is credible only in the range defined by the training data. In material modeling, this issue becomes more critical since the amount of data is usually limited, for instance, due to the high cost of conducting experiments. Below are two situations that typically appear in practice,

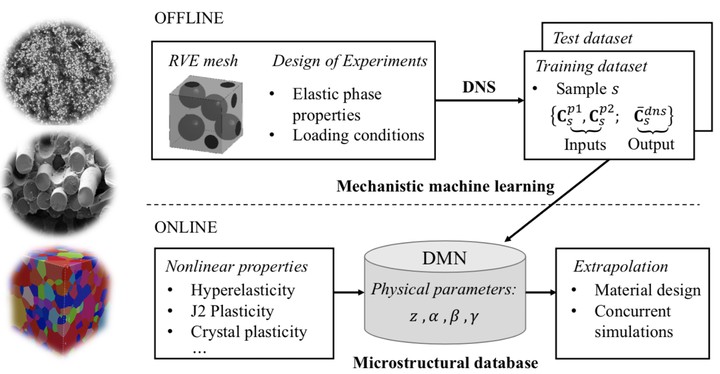

Deep material network (DMN) is proposed to address these problems by embedding mechanics/physics into the machine learning model. The key ingredients of DMN are a network structure for capturing the complexity of microstructural interactions, and a simple two-layer building block for reproducing the material physics.

Several equilibrium conditions and kinematic constraints need to be satisfied in the building block. Together with the the averaging condition and tensor rotations, they define the mechanics in the tranformation function of each building block. By applying this function iteratively through the network, the microscale information propagates from the bottom layer to the top-layer node, which represents the macroscale material.

The basic formulation of the overall stiffness tensor for a two-phase material with linear elasticity can be written as

The fitting parameters in the model are the activations and rotation angles , , . Since the two-layer building block is designed to have analytical solutions, one can derive the derivative of the output with respect to any fitting parameter or input. With linear elastic data obtained from direct numerical simulation or experiment, DMN can be effectively trained via stochastic gradient descent (SGD) and model compression algorithms.

The trained network can be extrapolated to unknown material and loading spaces in the prediction stage. For nonlinear materials, the system is solved via Newton’s method. Each Newton iteration contains one forward homogenization process and one backward de-homogenization process, and the flow of mechanical data in the forward and backward propagations are shown as below,

Comparing to other data-driven methods, DMN has the following intriguing features:

- Avoiding an extensive offline sampling stage;

- Eliminating the need for extra calibration and micromechanics assumption;

- Efficient online prediction without the danger of extrapolation

DMN has been applied to addressing various RVE challenges, such as hyperelastic rubber composite under large deformation, polycrystalline materials with rate-dependent crystal plasticity and various carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) composites. The network structure with physics-based parameters also provides a promising tool for materials design.

Recently, the original material network has been enriched with cohesive networks to handle materials with deformable interfaces. Same as before, the new cohesive building blocks have analytical solutions, so that the enriched network can still be optimized via SGD. An important application is on the interfacial failure analysis in CFRP composites, as well as particle-reinforced rubber composites.